August 2022 - Social Cost of Carbon: Seven Takeaways about the Most Important Climate Policy Metric You’ve Never Heard Of

/By Mimi Drozdetski and Samir Qadir

Credit: Bob Nichols/USDA

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities are a leading cause of climate change and its associated economic damages to society. With state and federal governments beginning to adopt more climate-focused policies, one tool is helping decision-makers better understand the economic implications of climate change impacts: the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC).

Estimating the Cost of Climate Change Impacts

An SCC analysis presents the cost, in dollars, of emitting one additional ton of a specific GHG into the atmosphere in a given year. Typically, SCC analyses develop separate cost estimates for emissions of individual GHGs and then sum them to get an overall SCC value, also sometimes referred to as the “social cost of greenhouse gases” or SC-GHG. In this article, we use SCC synonymously with SC-GHG.

Federal agencies started incorporating SCC estimates into their benefit-cost analyses conducted under Executive Order (E.O.) 12866 in 2008, following a court ruling that remanded a fuel economy rule to the Department of Transportation for failing to monetize GHG emission reductions. In 2009, President Obama launched an Interagency Working Group (IWG) to establish a standard value of SCC for use by the federal government. The IWG published its initial SCC values in 2010, which were revised in later years.

In principle, SCC takes into account the value of climate change impacts, including (but not limited to) changes in net agricultural productivity, property damage from increased flood risk and natural disasters, disruption of energy systems, human health effects, risk of conflict, environmental migration, and the value of ecosystem services. Incorporation of SCC ultimately allows agencies to understand the social benefits of reducing emissions of GHG, or the social costs of increasing such emissions in the policy-making process.

Economics, Demographics, and Climate Science All Play a Role

The SCC is estimated using specialized computer models, known as integrated assessment models, that analyze four types of information:

Socioeconomic Predictions

Climate Projections

Costs and Benefits

The Discount Rate

The models use information from a wide range of disciplines, including economics, demographics, and climate science. Socioeconomic indicators (i.e., population growth and economic growth rates, improvements in technology) allow for the prediction of future GHG emissions. Future climate projections (i.e., storms and flooding, drought, wildfire, sea-level rise) show how the climate may respond to increased emissions. The costs and benefits are estimated under these projected climate conditions and represent potential economic impacts to infrastructure, food production, water supply, and health. Models combine these various factors and use a discount rate to convert future damages into their present-day value.

Present Financial Benefits vs. Future Climate Damages

This graph shows how a lower discount rate results in a higher price per ton of carbon dioxide released. The Biden Administration has applied IWG’s Interim SCC estimates under a 3% average discount rate for CO2 emissions in a given year. Source: EPA, Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases

The discount rate indicates the value placed on present costs or benefits, relative to delayed costs or benefits that occur in the future. Using the discount rate, economists convert future climate damages into a present value. The present values of climate damages over time are then added up to determine the total economic cost of each ton of additional emissions. This approach allows direct comparison of damages occurring over large spans of time. The ability to compare the costs of GHG emissions in terms of present value provides policymakers with a valuable tool to evaluate decisions involving GHG emissions and mitigation.

A lower discount rate attributes a higher value to economic damage from future GHG emissions; conversely, a higher discount rate attributes a lower value to future economic damage. Using a low discount rate is therefore likely to result in a much larger SCC value than a higher discount rate. However, it is important to recognize that the choice of discount rate is also an ethical decision that should reflect societal concerns and priorities, and cannot be reduced to purely technical terms.

The SCC Influences Policies, not Prices

While the SCC favors the use of low-emission technology and infrastructure, it does not directly impact the price of gas, electricity, and emissions-intensive goods. Normally, market prices for these products and services do not automatically reflect the future economic damages caused by the emissions. This is where the SCC can play a crucial role by helping inform government spending and investment and, as a result, indirectly sway private companies’ and consumer behavior.

When evaluating policies that impact GHG emissions, the SCC can help quantify the economic costs or benefits associated with the emissions and efforts to reduce them. For policies that potentially increase emissions, the tonnage of increased emissions is multiplied by the SCC, and the result becomes part of the policy’s cost. For policies that cut emissions, the decrease in tonnage is multiplied by the SCC and included in the expected benefits of the policy.

In some cases, the economic costs or benefits take years to come to fruition compared to the upfront cost of implementation. It can be difficult to understand the link between policy and its contribution to climate change, but SCC bridges the gap in knowledge by adding a monetary value to the equation. Similarly, the SCC can be used to develop a fuller picture of the economic costs and benefits of other public- and private-sector actions that either increase or reduce GHG emissions, such as new industrial facilities, power plants, or GHG mitigation projects.

The SCC Has Evolved with Changing Administrations

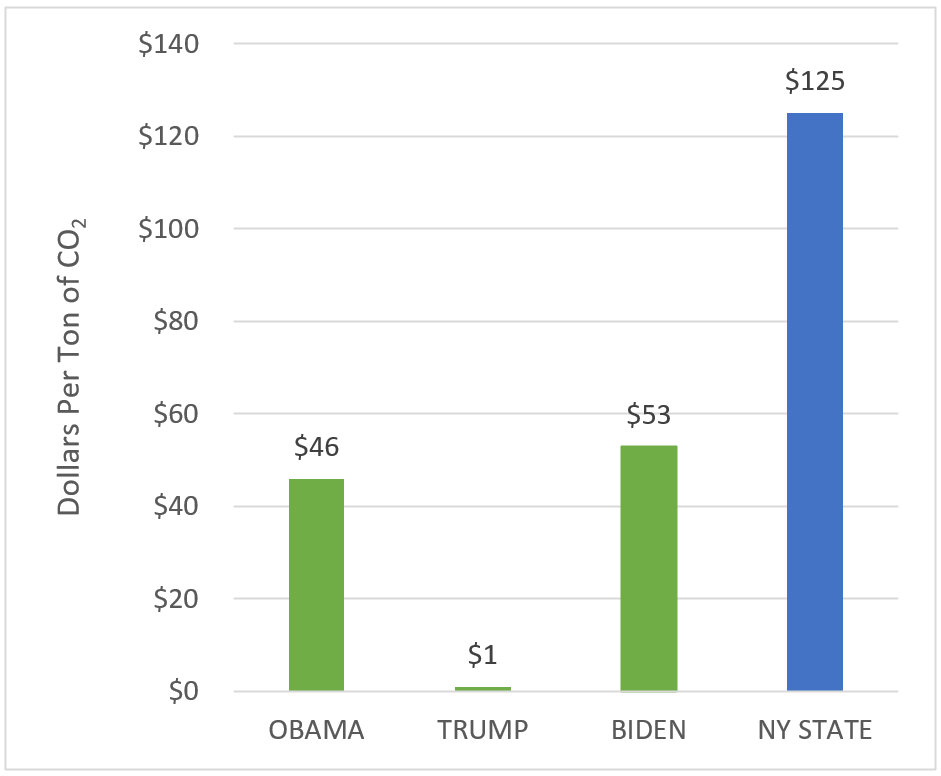

The Social Cost of Carbon under recent administrations, compared to the value used by the State of New York.

Prior to 2008, some federal agencies and departments developed and used their own SCC estimates. It was only under Former President Obama’s Administration that a unified SCC value was applied across the federal government. The Interagency Working Group (IWG) on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases was responsible for modeling the value and came up with an initial estimate of $30 per ton for 2025, eventually revising it to $46 per ton.

Under Former President Trump’s Administration, the SCC varied from $1 to $7 per ton, as the estimate only factored in domestic damages as opposed to the global impacts that the IWG had considered. President Biden reinstated the Obama Administration’s SCC value, after adjusting for inflation, at $51 per ton. The estimate is an interim figure, as the IWG is working to update the SCC to include more parameters.

On May 26, the Supreme Court allowed the Biden Administration to continue using the SCC, which is currently at $53 per ton. The decision came after a federal judge from Louisiana issued an order in early February prohibiting use of the higher value in response to a claim that the increased cost would cause economic harm to oil- and gas-producing states. With the Supreme Court’s ruling, federal agencies can use the Biden Administration’s interim SCC value in federal rules and decisions.

States are Starting to Use SCC

The use of SCC is not limited to the federal government, as states have also begun to incorporate this metric into their planning processes. Utilities commissions in Colorado, Minnesota, and Washington require the use of the federal SCC in resource planning. The Virginia state legislature passed the Clean Economy Act in April 2020, requiring the impacts of building fossil fuel-fired generators to be assessed using SCC.

Credit: Fre Sonneveld/UNSPLASH

Some states are even developing their own SCC estimates. In 2020, the New York State Department of Conversation (NYSDEC) issued state-wide guidance for the SCC with a central value of $125 per ton of CO2 . The value has served as a basis for “zero-emission credits” paid to electric utilities under state clean energy legislation. Most recently in May 2022, NYSDEC published values for the social cost of hydrofluorocarbons (SC-HFC) to offer guidance on the use of these potent GHGs that are commonly used as replacements for ozone-destroying chemicals.

Other states that have incorporated SCC into their decision-making include Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Illinois, Maine, Nevada, North Carolina, and Vermont.

Room for Improvement?

While the Biden Administration took a major step in increasing the SCC to account for the long-term harm caused by GHG emissions, some climate economists believe the value of $51 per ton is still too low. For example, one value that is still excluded from the economic assessments due to a lack of reliable data is the economic cost of human lives. Climate change is already being felt in historic heat waves, flooding, and wildfires around the world, making climate-related deaths an unfortunate reality. However, these figures remain largely unaccounted for in the SCC.

Climate science, and our understanding of the economic costs of climate change, is improving constantly. Therefore, we can expect that the application of the SCC will continue to evolve in informing policy, program, and project decisions that help mitigate GHG emissions and reduce their impacts to human society.

Potomac-Hudson Engineering, Inc. (PHE) has been providing environmental consulting services to government and private sector clients for over 30 years. Our expertise includes environmental planning and analysis and environmental compliance, with a focus on GHG emissions and climate change. We have conducted GHG and social cost of carbon analyses for large and small infrastructure projects , including commercial-size energy projects. To learn more about how PHE can help you reduce your GHG emissions, improve your sustainability posture, and prepare to respond to the challenges posed by climate change, contact Samir Qadir at samir.qadir@phe.com.

Samir Qadir is an associate Principal and senior engineer at PHE, working on topics related to sustainability, environmental planning, and compliance. He has worked on lifecycle GHG emissions and social cost of carbon calculations for major infrastructure projects, developed of strategic sustainability plans and solid waste management and recycling plans for federal facilities, and supported energy auditing and benchmarking efforts at residential and commercial buildings.

Mimi Drozdetski is an environmental analyst at PHE, working on National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) documentation and data management. She received her Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science and Geographical Sciences from the University of Maryland. Her previous experience includes lifecycle analysis and supply chain research, as well as agricultural production.